Realign or Replace? What is the difference and what does it mean for you?

When one side of the knee is worn more than the other, two main surgical options exist: osteotomy, which realigns the leg to preserve your own joint, and unicompartmental knee replacement (UKR)

Osteotomy vs Unicompartmental Knee Replacement (UKR): what the Australian registry shows—and what it means for you

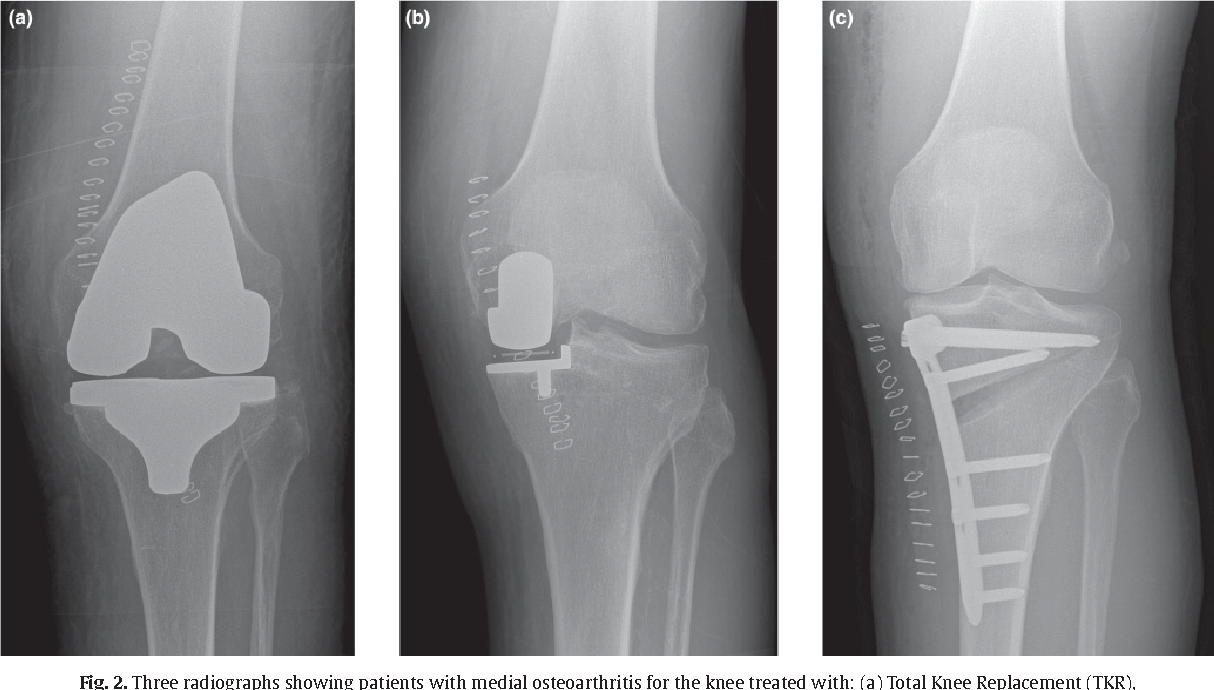

When one side of the knee is worn out more than the other, two surgical options are often on the table:

- Osteotomy (usually a high tibial osteotomy, HTO): realigns the leg to shift load off the worn compartment, preserving your native joint.

- Unicompartmental knee replacement (UKR): resurfaces only the damaged side with metal and plastic.

Below is a plain-English guide to how they differ, who they suit, and what the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry (AOANJRR) and recent literature say about outcomes—including what happens if either option later needs a total knee replacement (TKR).

The big picture: durability and “next-step” surgery

How often are UKRs revised over time?

AOANJRR reports that UKR has a higher revision rate than TKR overall. At 20 years after UKR, 27.1% have been revised; in patients younger than 55, 42.6% are revised by 20 years. By contrast, patients <55 who have a primary TKRhave a 15.0% 20-year revision risk. AOANJRR

How often do osteotomies convert to TKR?

The AOANJRR’s Knee Osteotomy Registry (national, opt-out) shows conversion to TKR is uncommon—<2% cumulative at 6 years. “Valgising” tibial osteotomy (the standard medial opening-wedge HTO for medial OA) had a substantially lower risk of conversion than other osteotomies (HR 0.23) and a lower risk than medial UKR for ending up in a TKR (HR 0.19). Revision of the osteotomy itself occurred in ~3.3%, mainly for delayed union or under-/over-correction. ISAKOS

If a UKR does need revising, how does a conversion to TKR perform?

AOANJRR’s 2024 Revision Supplement shows that when UKR is revised to TKR, the risk of another revision (a “2nd revision”) is: 2.5% at 1 year, 6.4% at 3 years, 8.6% at 5 years, and 12.4% at 10 years. Bottom line: if a UKR fails, converting to a TKR has acceptable, comparatively favourable re-revision rates. AOANJRR

Who is best suited to each?

Osteotomy (HTO/DFO)

Best for:

- Younger, active patients with unicompartmental osteoarthritis and correctable malalignment (most commonly varus for medial OA).

- Good range of motion and manageable patellofemoral symptoms. Joint preservation is a priority. Arthroplasty Journal+1

Common contraindications (or poor candidates):

- Inflammatory arthritis, severe tricompartmental disease, gross instability that can’t be addressed, very limited motion, or poor bone quality. (Some are relative and case-by-case.) Arthroplasty Journal

What to expect:

- Goal: unload the worn side to relieve pain and slow progression.

- Recovery: bone healing is required; return to impact activity is often achievable.

- Future options: because your joint is preserved, conversion to TKR—if ever needed—is usually straightforward; registry data suggest low medium-term conversion rates. ISAKOS

Unicompartmental Knee Replacement (UKR)

Best for:

- Patients with isolated medial or lateral compartment OA, intact or functional cruciates (particularly ACL for many designs), correctable deformity, and minimal disease elsewhere. Modern consensus has widened indications beyond the classic “older, thin, low-demand” patient, but careful selection remains crucial. ScienceDirect+2Arthroplasty Journal+2

Common contraindications (or caution):

- Inflammatory arthritis, fixed deformity (e.g., >10° varus or >5° valgus), severe stiffness, marked patellofemoral or opposite-compartment disease, or gross instability/ACL deficiency (design-dependent). These are evolving and often relative—discussed individually in clinic. Arthroplasty Journal+1

What to expect:

- Benefits: smaller operation than TKR, quicker early recovery, more “natural-feeling” knee in the right candidate.

- Trade-off: higher lifetime revision risk than TKR, especially in younger patients; if it fails later, conversion to TKR is the standard—and performs acceptably on registry follow-up. AOANJRR+1

Take-home

- Osteotomy: joint-preserving, ideal for the younger malaligned knee with localized wear; very low medium-term conversion to TKR in Australian data.

- UKR: less invasive than TKR and often faster recovery, but higher long-term revision risk—especially if you’re under 55. If it does fail, UKR→TKR performs well on our registry.

- Your best option depends on age, alignment, ligament status, pattern of arthritis, activity goals, and expectations. A tailored exam, standing alignment films, and discussion of pros/cons against your goals is essential.

Conversion to Total Knee Replacement after undergoing Osteotomy or UKR results in similar outcomes, although there may be slightly better early return to function and less need for augments in the osteotomy to TKR group of patient